PETER KUTIN

Špela Cvetko spoke with Peter Kutin during the SONICA 2020 festival in Ljubljana.

Welcome to another edition of SONICA’s artist podcast in which our guest for today is Peter Kutin, Vienna based artist, who works with sound across genres, but more importantly, utilizes it across different forms of art practice. From live performances and installations to film, radio, theatre, and dance stages. He is also a founding member of Ventil records, the organization Velak, which is the platform for experimental music, and at SONICA he is presenting two works. One will be part of an exhibition in the Equrna gallery and is part of the Decomposition Series, called Heat. And the other performance will be on the 26th of September at the Ljubljana Museum of Modern Art, where he will present AV performance, called ROTOЯ.

Peter, it is really great that we could catch you in Ljubljana in real-time, most of the other artists did not make it, sadly, due to travel restrictions. But let’s step back a bit and could you tell us how did you start to make works at the intersection of art and music?

There was never really an initial plan to do that, it was more through experience, and through following your instincts. Sometimes having luck and just seeing that things like image and sound relate to each other very strongly or it depends a lot on how you arrange it and which importance you give the image and the sound. This field started to interest me and some colleagues around me more and more and so we just jumped into this and did some projects, see how it goes. It somehow developed on its own, there was never really an initial plan. I try to be open, keep my eyes and ears open to what interests me or to what touches me, or does something to my brain that I find interesting, and then just wait for the moment to do something. It is more like, yeah, I’m working with the sound all the time, it is my daily job, like a carpenter works with wood and sometimes you do pieces that have more ideas or sometimes there is a big idea behind it.

Did your practice as it looks now started at the University of Applied Arts, where you studied, so did it come from a more institutionalized educational background, when you knew new theories about music that you previously did not or was more like self-thought "let’s see where sound and field recordings take us".

Well in my case the university was more a place where I could use a studio because I didn’t have any gear and I didn’t have a laptop at the time I started studying – it was more than ten years ago so all this stuff was more expensive. I was there more because of the gear and the context and it was more an auto-didactic process. I did not get out of university with the necessity to become an artist. Not at all actually, it took a long time to find this path again. I think I took a few years off art after the university because I did not like this academic approach so much.

I wanted to just mention: your works – past and current – deal a lot with outside the gallery white box content in that you’ve for a few years extensively traveled the world and collected recordings from quite extreme – sometimes desolate, sometimes bustling with life places and I am wondering if there is a certain reason or did you thought about why you’re drawn to extreme places.

Yeah, this is a long long story, there are maybe two sides to it, the first that I really got fascinated with recording in the field, like what you can do with technics. It was also the time before everybody had a Zoom recorder, it was more to collect some gear and I got kind of hooked with this and for a long time after the university I got drowned to innovative journalism and really meeting people, doing almost journalistic work but also combined with field recordings. Some places I went to were even the warzones, so maybe I have this rather necessity to go to these extreme things, also in the music sometimes. When you start to feel unsafe, it is also opening many possibilities. But traveling-wise I stopped a lot since I decided to straight go for art and don’t do the journalistic approach because I couldn’t do both at the same time and sometimes it got really, really rough. I didn’t see the sense of what can you do with journalistic work anymore – I lost the faith in it a bit.

So keeping up with this point, field recordings in itself are sometimes seen as delegated to the realm of either someone that makes sounds for advertisements or let’s say as Foley techniques in film and television or in its academic context or at least academic art where the focus is on the gear or what the sounds tell us without us being in that space. And I am wondering when you record for yourself, do you go out with the purpose to find something, or is it more of a discovery, seeing where it takes you.

When I started doing field recordings, it was always like that – taking the recorder with me and doing whatever interesting could be found and record it. But I stopped that since ten or more years, I don’t touch the recorder if I don’t have a clear idea of what I want to record. So now the recordings are always related to the piece or a project or an idea.

And when you’re talking about your projects, your pieces, a lot of them, at least in the last five years, more or less, deal a lot with light and movements. Let’s say light and kinetic aspects of what a physical material can do. You are doing a performance piece on the 26th, called ROTOЯ. Could you, before I go into a lengthy description, give the listeners an idea of how does that project look and what does it do.

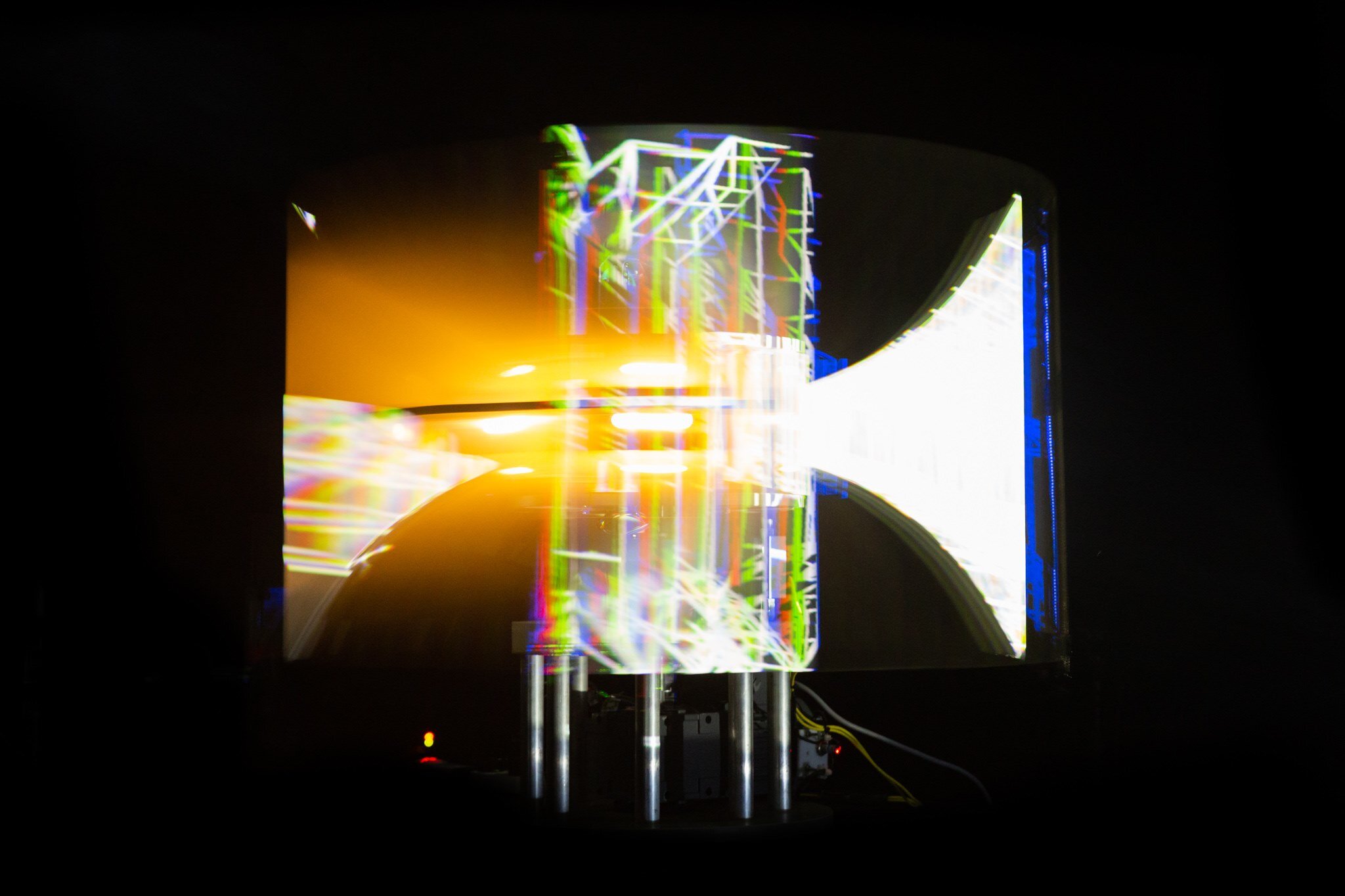

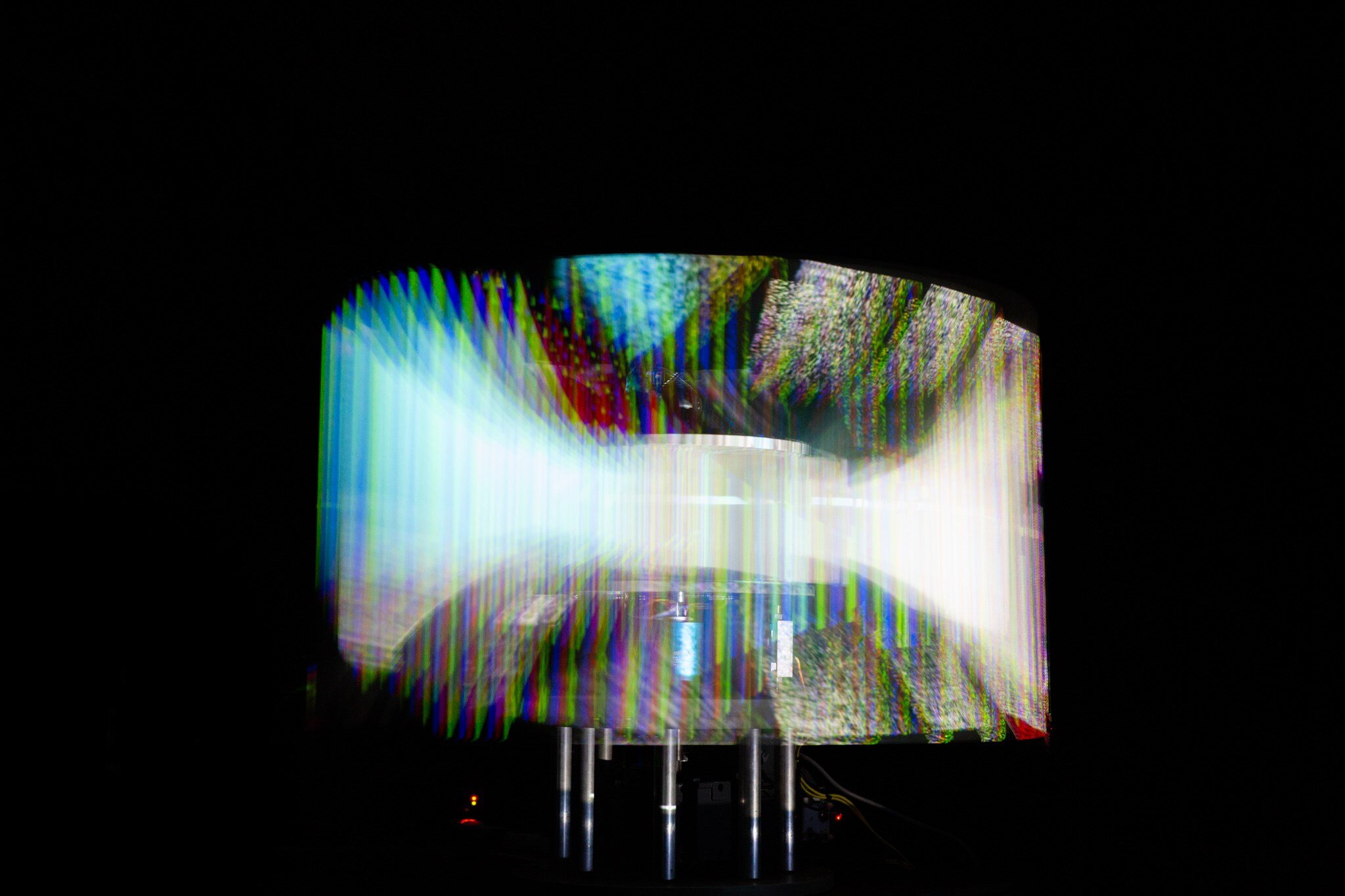

As you said, ROTOЯ is a kinetic sculpture. It started a few years ago, I was interested in working with rotating sound sources, meaning speakers that actually move on a circular path. Because usually in the modern music you have speakers that are static and then the sound moves invisibly through space and this is supposed to be really cool or something, I never really got aesthetically something out of it other than a technical show-off aspect of it. I thought it would be interesting to really see speakers traveling in the space very fast. So I started working on a few projects and I finished one. One sculpture that was looking like a windmill but with loudspeakers instead of wind. And for the ROTOЯ it is sort of a similar concept but it's rotating around the vertical axes so it is a little like Brion Gysin’s Dream Machine. It is four rotating speakers. For this project I worked with Patrik Lechner, he is the person behind the video technique of this project, because – now it gets a little bit complex but maybe someone can follow me – so what we do is map the 3D model of the object on the object itself, so that is covered by itself but with an artificial image. And the ROTOЯ can be spun up to 3,5Hz, which is 3,5 rotations per second, it's pretty fast. And the projection, the software of the video always knows exactly where the position is so it can travel at the same speed. The original ROTOЯ travels with 3,5Hz and the projection can also travel with 3,5Hz so it is a unified object. But you can also slow down the projection and then you have two mediums: the object as a medium and then an image as a medium. And they go with different speeds so it’s like a polyrhythm and it opens really strange visual corridors at this moment. I am very interested in these heterochrony situations where different mediums follow very different speed and are not synchronized anymore and in-between these different speeds there is a lot of things to find I think.

Just from a purely technological viewpoint, you stated that the speakers are always around us but we don’t see them and they are a kind of a showcase of ‘let’s see how much money I can put into something that we don’t perceive visually’, we do perceive the result that is coming from the object but the object itself is not as important. And in the videos of the ROTOЯ and the Torso, the previous iteration of ROTOЯ that you were referring to, the speakers are put into the center or on the stage, they are not anymore the object, they become the subject. How do you feel as an artist or a performer which is controlling this piece, but not being on the stage with it? Is it important for you to diminish your human presence, your personal authorship over this, and leave the audience with the object?

Yeah, this is extremely important for me. To not be present as a body, as a human white male body on stage, because I think it always distracts [the audience's] perception a lot. I mean of course if you’re a great performer, whose performance on stage creates something transcendent, like David Bowie or people that need to be present [then] their presence makes perfect sense. But I work with sound and my presence on stage is really not important. And this is one of the points [that] I try to make. These sculptures, as you said, are becoming almost a performative act, a subject on stage that is supposed to seduce the listener. I really like this aspect to it a lot, I used to play in dark rooms, where there is no light or try to combine visuals and this went further and further and I like this situation where you’re confronted with just an object but it is still sort of threatening because it creates wind because the rotation is fast, it doesn’t feel super safe in there. I don’t want to go further with explaining but the point to not be present is very important and is very strong.

Not only ROTOЯ, but in a lot of your pieces, there is a distinct feeling, I don’t know if it’s from your viewpoint, we are not given the context, if this is a political work and how and when should it be placed, or is it a historical leaning work or whatever, but it literarily assaults our senses, for example, the ROTOЯ with the sound, with the whooshing. Do you ever think of imbuing the audience with the certain thing when they see and experience this work, for example, danger, as you’ve already referenced, or maybe excitement? Is there this sensual point of view or is it for you just the visual aspect that is quite complex enough?

Well, I can just take myself and the people that I work with on a project as a reference point. If it’s getting interesting for me and I get feedback from them, then I am happy. Then I think it seems to work, it does something for me. If it feels maybe uncomfortable or enjoyable, I really don’t know, it really depends on how the composition goes. This is part of how you compose these things. You have the movement, the speed; it can be very hectic or also very relaxing, depending on how far you push it. The same with the sound, the same with the light, the same with the video. So it depends on where you want to go, I still very think piece-oriented, to have a start and an ending, so if people want to stay longer they can get on a journey and maybe go through more than just one emotional component.

But also before we see the work ROTOЯ, we will see the exhibition at the Gallery Equrna, which is running from the 8th until the 27th of September and there you have work called Heat, which is in the series called Decompositions, the fifth in the series, right?

Mhm.

And it's basically a thermal-imaging video showing orchestral instruments and the musicians playing them. It seems that in all these Decompositions, you are using technology in a way that is not intended to use. Why the heck would we look at an orchestra with a thermal imaging camera? How do you even get an idea to do it – to subvert the form of technology and what do you think can come from that in terms of a new aspect of looking at the artwork?

In these Decomposition Series, I always work with the same project partner Florian Kindlinger so we’re basically doing this together. As you said, it's always pushing technology or use it as a prosthesis for our senses to discover something that is usually not graspable for humans. Then try to make a piece out of it in a poetic or in a compositional context. Where the need for this comes from… I don’t know, it is probably to be noisy, to try to find stuff that surprise you. All these projects we set off on the sailing ship, either you hit land or you just don’t. it is not a random process, we talk about it long, we do the research if it could work, but then we start and there is not really a test before, we just go on this boat, and then you need to navigate it. That is what makes it interesting, for us it always has an “expeditionary” character to it.

Colonizing the unknown. (Laughter)

Yeah, it is not really colonizing but we’re very childish with this, we are just happy to see something, find something and of course, these hidden layers of our reality are very interesting for me in general. All these frequencies that are kept out of our way but are still there. The technological world follows this path where stuff you don’t hear, you don’t see can be packed away somewhere, even though it is extremely loud. High frequency pitched signals above your hearing, above 20kHz. There is sometimes in a room at 105db, which is super loud but you cannot hear it so people don’t care about it. I think it’s interesting to look at that sometimes. And for Heat it was interesting to see where is this warmth created on instruments, can you heat it up and how long is it there.

The recording of the interview features excerpts from Decomposition IV (Variations on Bulletproof Glass) and Decomposition V (Heat) by Peter Kutin & Florian Kindlinger.

Photos of exhibiton and ROTOR by Kaja Brezočnik.

The podcast was produced with support from SIGIC - Slovenian Information Music Center.

Peter Kutin is an artist supported by SHAPE Platform, which is co-funded by the Creative Europe.

![eu_flag_creative_europe_co_funded_vect_pos_[cmyk]_right-[Converted].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5b616fe19772ae414b277bbf/1616770976936-VC6DRTMLKGQSC7NN065M/eu_flag_creative_europe_co_funded_vect_pos_%5Bcmyk%5D_right-%5BConverted%5D.jpg)